The Optic Nerve: Anatomy, Pathology, and Management of Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy

Introduction: The Data Cable of the Human Visual System

Vision is often described as the most dominant of the human senses, yet the eye itself is merely the instrument that captures light. The actual act of "seeing"-the interpretation of images-occurs in the brain. The critical bridge connecting these two entities is the optic nerve. To understand the optic nerve, one can visualize a high-speed fibre-optic data cable. Just as a cable transmits digital information from a camera to a computer for processing, the optic nerve transmits bio-electrical impulses from the retina to the visual cortex of the brain.

When this cable functions correctly, we perceive the world in sharp, continuous images with a wide field of view. However, unlike a digital cable that can be replaced if frayed, the optic nerve belongs to the Central Nervous System (CNS). In adult humans, once the fibres of the optic nerve are severed or die, they do not regenerate. This biological reality makes the preservation of optic nerve health one of the most critical priorities in modern ophthalmology.

The most common and devastating condition affecting this structure is a group of diseases collectively known as Glaucoma. Often termed the "Silent Thief of Sight," this condition slowly erodes the fibres of the optic nerve, frequently without causing pain or noticeable symptoms until significant vision has been irreversibly lost. Understanding the anatomy of the nerve, the mechanism of damage, and the medical interventions available is essential for every patient, particularly those over the age of 40 or those with a family history of eye disease.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Optic Nerve

The Structure of Sight

The optic nerve, clinically known as Cranial Nerve II, is a paired nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. It is comprised of approximately 1.2 million retinal ganglion cell axons. These axons are long, thread-like extensions of the nerve cells found in the retina.

The journey of visual information begins at the photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the retina. These cells convert light energy into electrical signals. These signals are passed to the retinal ganglion cells, whose axons converge at the back of the eye to form the optic disc (also known as the optic nerve head). This is the specific point where the nerve leaves the eye. Because there are no photoreceptors at the optic disc, every human eye has a natural "blind spot," though the brain compensates for this, making it unnoticeable in daily life.

The Vulnerability of the Optic Disc

The optic nerve head is the most vulnerable point in this system, particularly regarding pressure. The eye is a pressurized globe, maintained by a fluid called aqueous humor. This pressure, known as Intraocular Pressure (IOP), is necessary to keep the eye inflated and spherical. However, the optic nerve must pass through a sieve-like structure called the lamina cribrosa as it exits the eye.

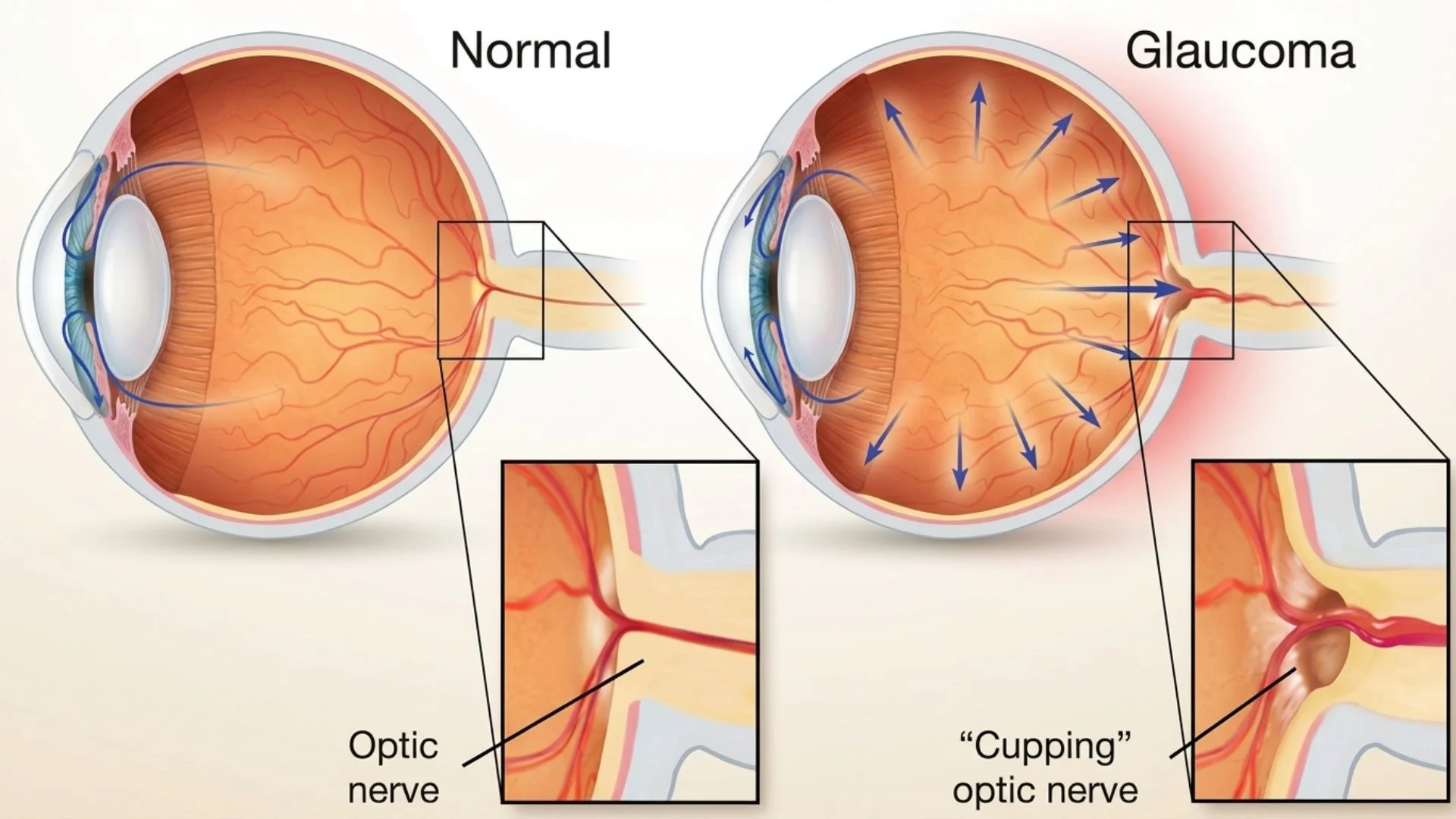

When IOP becomes too high, or if the blood supply to the nerve is compromised, the delicate nerve fibres are compressed against the lamina cribrosa. This mechanical stress, combined with vascular insufficiency (lack of blood flow), leads to the death of the nerve cells. This process is the fundamental pathology behind glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

The Cup-to-Disc Ratio

Ophthalmologists often refer to the "Cup-to-Disc Ratio" when assessing optic nerve health. Imagine the optic nerve head as a teacup seen from above. The "disc" is the rim of the cup, consisting of healthy orange/pink nerve tissue. The "cup" is the empty, pale center. In a healthy eye, the cup is small, and the rim of healthy tissue is thick.

As glaucoma progresses and nerve fibres die, the rim thins, and the central cup enlarges. This "cupping" is a hallmark sign of optic nerve damage.

A larger cup-to-disc ratio is often the first clinical sign of glaucoma, sometimes appearing before the patient notices any vision loss.

The Pathology: Glaucoma and Optic Nerve Damage

Understanding the Mechanism of Damage

Glaucoma is not a single disease but a group of ocular disorders characterized by progressive optic nerve damage. While high intraocular pressure (IOP) is the most significant risk factor, it is important to understand that optic nerve damage can occur even with normal eye pressure in susceptible individuals.

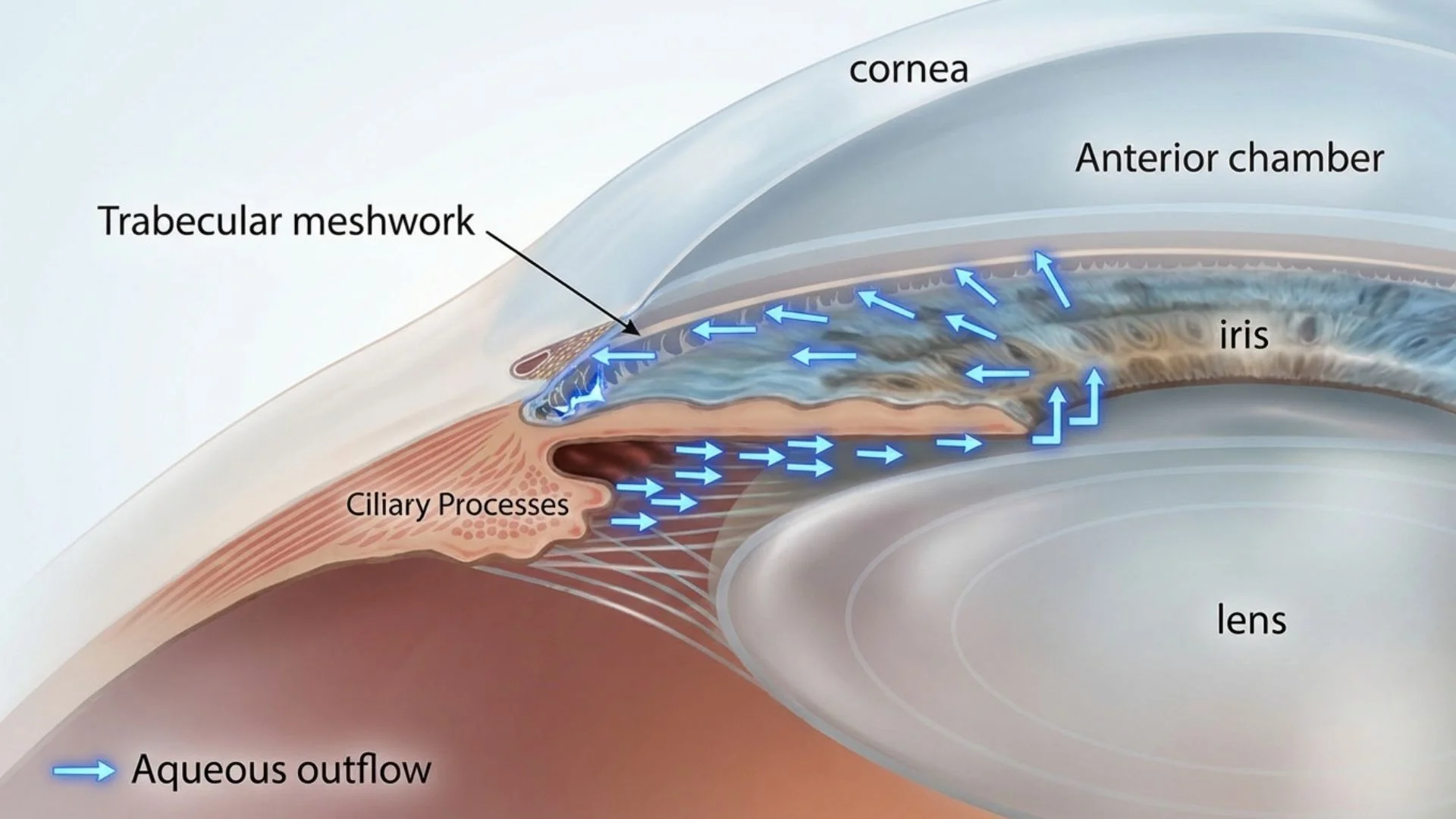

The pathology is generally driven by an imbalance in the production and drainage of aqueous humor. The eye constantly produces this fluid, which drains out through a specialized filter called the trabecular meshwork located at the angle where the cornea and iris meet.

Fluid Buildup: If the drainage system becomes blocked or inefficient, fluid accumulates.

Pressure Elevation: This accumulation raises the IOP.

Mechanical Compression: The increased pressure pushes against the optic nerve head.

Apoptosis: The stress causes the retinal ganglion cells to undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death).

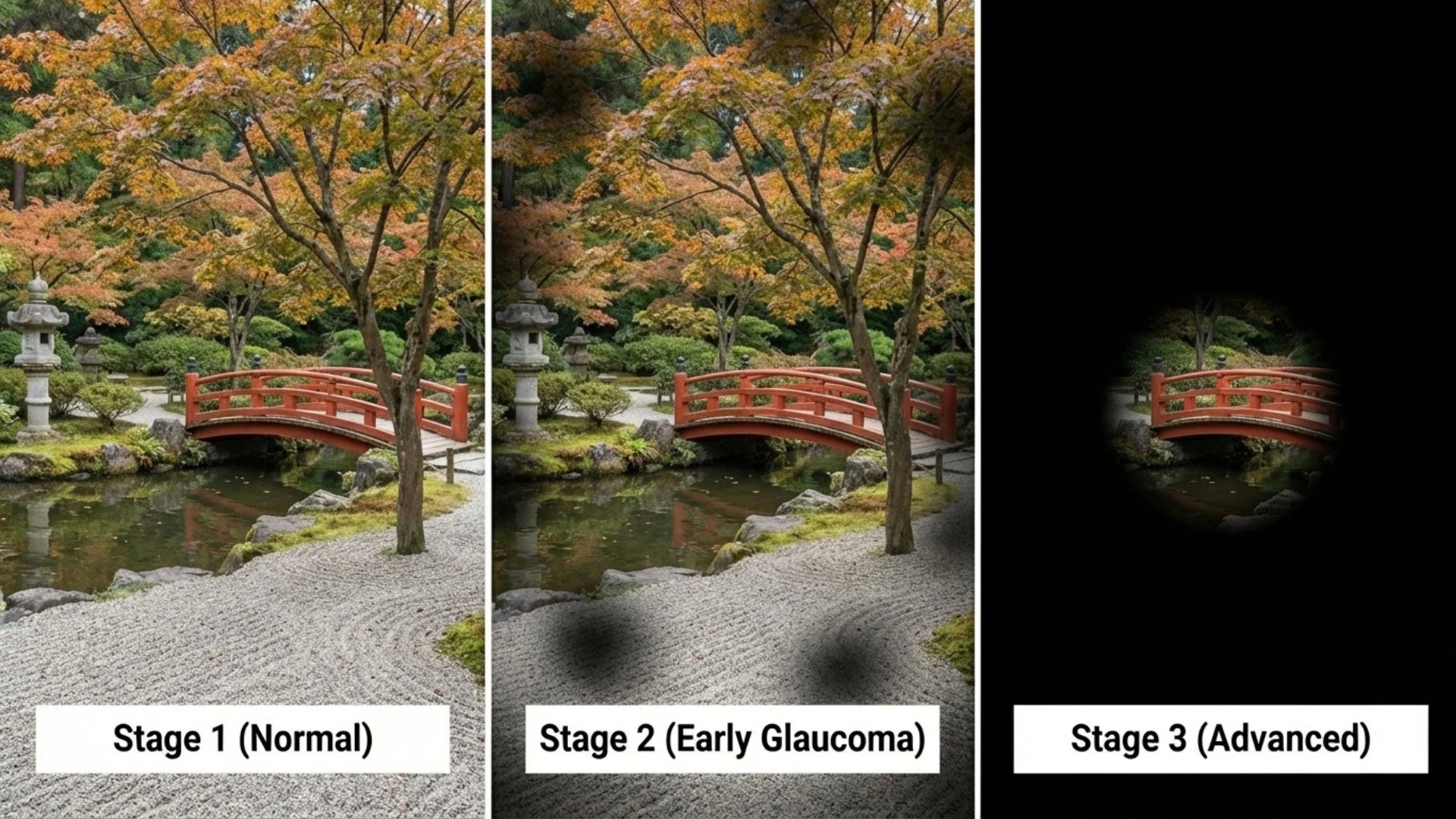

Vision Loss: As fibres die, the connection between the eye and brain is severed, usually starting with peripheral (side) vision.

Types of Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG)

This is the most common form of the condition worldwide. In POAG, the drainage angle remains anatomically "open," but the trabecular meshwork becomes clogged over time, similar to a slow drain in a sink. The pressure rises gradually, causing slow, painless damage to the optic nerve.

Symptoms: Usually none in early stages. Later, patchy blind spots in peripheral vision occur.

The "Silent" Nature: Because the loss starts peripherally and the brain fills in the missing gaps, patients often lose up to 40% of their optic nerve fibres before noticing a problem.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma

This is less common in the West but more prevalent in Asian populations. Here, the drainage angle is physically blocked by the iris, causing a complete or partial obstruction.

Acute Angle-Closure: A medical emergency where the pressure spikes suddenly. Symptoms include severe eye pain, nausea, vomiting, halos around lights, and blurred vision. Immediate treatment is required to prevent permanent blindness within hours.

Chronic Angle-Closure: The angle closes slowly over time, mimicking the symptoms of open-angle glaucoma but with a different anatomical cause.

Normal-Tension Glaucoma (NTG)

In this variation, optic nerve damage occurs despite the eye pressure being within the statistically "normal" range (usually 10-21 mmHg). This suggests that the optic nerve in these patients is hypersensitive to pressure or suffers from poor blood perfusion. Treatment still focuses on lowering IOP to a level lower than "normal" to relieve stress on the nerve.

For more information on the classification of glaucoma, refer to the American Academy of Ophthalmology clinical guidelines.

Diagnostic Procedures for Optic Nerve Health

Because optic nerve damage is irreversible, early detection is the cornerstone of management. Modern ophthalmology employs a suite of advanced diagnostic tools to visualize the nerve structure and assess its function.

1. Tonometry (Pressure Measurement)

This measures the Intraocular Pressure (IOP). The "Gold Standard" is Goldmann Applanation Tonometry, where a small prism gently touches the anaesthetized surface of the eye to measure resistance. However, IOP fluctuates throughout the day, so a single normal reading does not rule out glaucoma.

2. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT has revolutionized the diagnosis of optic nerve conditions. It is a non-invasive imaging technique that uses light waves to take cross-section pictures of the retina.

RNFL Analysis: The OCT measures the thickness of the Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer (RNFL). In early glaucoma, this layer thins out as nerve axons die.

Precision: OCT can detect thinning of the optic nerve fibres years before it becomes apparent on a visual field test or visible to the naked eye during an exam. It allows for quantitative tracking of disease progression down to the micron level.

3. Visual Field Assessment (Perimetry)

While OCT looks at structure, perimetry looks at function. This test maps the patient's complete field of vision. The patient stares at a central target and presses a button whenever they see a flash of light in their peripheral vision.

Defect Patterns: Glaucoma produces specific patterns of vision loss, such as nasal steps or arcuate scotomas (blind spots shaped like an arc).

Progression Analysis: Repeated tests over time tell the specialist if the vision loss is stable or getting worse.

4. Gonioscopy

This exam allows the ophthalmologist to view the drainage angle of the eye directly. Using a special mirrored lens, the doctor can determine if the angle is open, narrow, or closed, which is critical for diagnosing the type of glaucoma and deciding the treatment path (e.g., laser vs. drops).

Procedures and Medical Interventions

The primary goal of all treatments for optic nerve damage related to glaucoma is to lower Intraocular Pressure (IOP). By lowering the pressure, we reduce the mechanical stress on the nerve, aiming to halt or significantly slow the rate of cell death. It is important to note that treatment preserves remaining vision; it cannot restore vision that has already been lost.

Pharmacological Interventions (Eye Drops)

For most patients, prescription eye drops are the first line of defense. These medications work via two main mechanisms: decreasing fluid production or increasing fluid outflow.

Prostaglandin Analogs: These increase the outflow of fluid through a secondary drainage pathway (the uveoscleral outflow). They are often the first choice due to their effectiveness and once-daily dosing.

Beta-Blockers: These work by reducing the production of aqueous humor by the ciliary body.

Alpha-Adrenergic Agonists: These have a dual action of reducing production and increasing outflow.

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: These reduce fluid production.

Rho Kinase Inhibitors: A newer class of drugs that increases outflow through the trabecular meshwork.

Adherence to medication is critical. Skipping doses allows pressure to spike, causing cumulative damage to the optic nerve.

Laser Procedures

When drops are insufficient, or if the patient struggles with compliance/side effects, laser therapy is often the next step.

Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty (SLT)

Used primarily for Open-Angle Glaucoma. The laser targets specific cells in the trabecular meshwork.

Mechanism: It does not "burn" holes; rather, it stimulates a biochemical immune response that "cleans out" the meshwork, improving drainage.

Benefit: It is a low-risk, repeatable procedure that can often reduce or eliminate the need for eye drops for a period of time.

Laser Peripheral Iridotomy (LPI)

Used for Angle-Closure Glaucoma or patients with narrow angles.

Mechanism: The laser creates a microscopic hole in the outer edge of the iris.

Benefit: This creates a bypass channel for fluid to flow from behind the iris to the front, equalizing pressure and preventing the iris from blocking the drainage angle. It is often performed prophylactically in high-risk eyes to prevent acute attacks.

Surgical Interventions

When medication and laser therapies fail to halt the progression of optic nerve damage, surgical intervention becomes necessary to create a new drainage pathway.

Trabeculectomy

Considered the "Gold Standard" in glaucoma filtration surgery for decades. The surgeon creates a guarded flap (trapdoor) in the sclera (white of the eye). This allows fluid to bypass the clogged meshwork and drain into a reservoir (bleb) under the conjunctiva.

Efficacy: Highly effective at lowering pressure.

Risks: Higher risk of hypotony (pressure too low), infection, or scarring compared to newer methods.

Tube Shunt Surgery (Glaucoma Drainage Devices)

A flexible plastic tube is inserted into the eye to drain fluid into a silicone plate implanted on the eye's surface. This is often reserved for complex cases or eyes that have had previous surgeries.

Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS)

This represents the most significant advancement in glaucoma surgery in recent years. MIGS procedures use microscopic instruments and tiny incisions.

Stents and Shunts: Tiny titanium or collagen stents (smaller than an eyelash) are implanted into the trabecular meshwork to bypass obstructions.

Safety Profile: These surgeries are safer than traditional trabeculectomy, with faster recovery times, making them suitable for patients with mild to moderate optic nerve damage. They are frequently combined with cataract surgery.

For an in-depth review of MIGS technologies, the Journal of Ophthalmology provides extensive clinical data.

Remedies, Lifestyle, and Neuroprotection

While medical and surgical interventions tackle the physical pressure in the eye, patients often ask what they can do in their daily lives to support optic nerve health. While there are no "home remedies" that cure glaucoma or regrow nerve fibres, certain lifestyle modifications can support overall ocular health and potentially act as neuroprotective factors.

1. Dietary Considerations

Research suggests that oxidative stress plays a role in the death of retinal ganglion cells. A diet rich in antioxidants may help support the optic nerve environment.

Nitrates: Green leafy vegetables (spinach, kale, collard greens) are high in dietary nitrates. Studies suggest higher intake of dietary nitrates is associated with a 20-30% lower risk of primary open-angle glaucoma, particularly those with early visual field loss.

Antioxidants: Vitamins C, E, and A, along with Zinc, are vital for ocular health.

Gingko Biloba: Some studies indicate that Gingko Biloba extract may improve blood flow to the optic nerve, potentially benefiting patients with Normal-Tension Glaucoma, although this should be discussed with a doctor before starting.

2. Exercise and Intraocular Pressure

Aerobic exercise (walking, swimming, jogging) has been shown to transiently lower intraocular pressure and improve blood flow to the optic nerve.

The Caution: Conversely, isometric exercises (heavy weightlifting) and positions where the head is lower than the heart (inversion tables, certain Yoga poses like the headstand) can significantly increase IOP and intracranial pressure. Patients with advanced optic nerve damage should avoid these activities.

3. Sleeping Position

There is evidence to suggest that sleeping with the head slightly elevated (using a wedge pillow) may lower IOP during the night compared to lying flat. Additionally, patients should avoid sleeping with their face pressed directly into the pillow, which can mechanically raise eye pressure.

4. Systemic Health Management

The optic nerve requires a robust blood supply. Conditions that affect vascular health can accelerate optic nerve damage.

Blood Pressure: Both high blood pressure and low blood pressure (hypotension) are risk factors. While high pressure damages vessels, extremely low blood pressure (especially at night) can reduce perfusion pressure to the optic nerve, starving it of oxygen.

Sleep Apnea: There is a strong correlation between Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) and glaucoma. Treating OSA with CPAP therapy is crucial for optic nerve oxygenation.

Diabetes: Poor blood sugar control damages micro-vessels throughout the body, including the eye.

5. Neuroprotection Research

The future of optic nerve management lies in neuroprotection-therapies designed to make the nerve cells more resilient to stress, and neuroregeneration-therapies to regrow lost fibres. While currently in experimental stages or clinical trials (such as the use of Nerve Growth Factors), this area represents the hope for restoring vision in the future. Current "remedies" focus on preservation.

For updates on neuroprotection research, reputable sources like the Glaucoma Research Foundation offer summaries of ongoing clinical trials.

Summary: Vigilance is Key

The optic nerve is the unsung hero of human vision, a complex biological cable that, once damaged, cannot currently be repaired. Because conditions affecting the optic nerve are often asymptomatic until late stages, the only true "remedy" is early detection through regular comprehensive eye examinations.

A screening involves more than just reading letters on a chart; it requires specific checks of the eye pressure and the optic nerve structure. By combining advanced diagnostics (OCT, Visual Fields) with a spectrum of treatments ranging from drops to microscopic implants, modern ophthalmology can successfully preserve vision for the vast majority of patients, allowing them to maintain their quality of life.

Important Medical Notice: This information provides general educational content about refractive errors and should not replace professional medical advice. For personalized assessment and treatment recommendations, please schedule a consultation with our eye care specialists. All vision correction methods including spectacles, contact lenses, and surgical procedures carry risks and limitations. Contact lenses carry risks of infection and corneal complications. Surgical corrections carry risks including infection, vision loss, need for additional procedures, and in rare cases permanent blindness. All options should be thoroughly discussed with a qualified ophthalmologist.

Licensed Healthcare Service: Our clinic operates in accordance with healthcare regulations. For questions about our services or to book an appointment, please visit our contact page or call during operating hours. For medical emergencies, contact emergency services immediately.

When to Seek Professional Care

Progressive damage to the optic nerve from elevated eye pressure gradually erodes peripheral vision without pain or early warning signs, making regular screening essential for preserving sight. Please visit the doctor if you have any of the following symptoms:

Gradual loss of peripheral or side vision

Patchy blind spots in visual field areas

Severe eye pain with nausea and vomiting

Halos appearing around lights especially at night

Blurred vision accompanied by redness and discomfort

Comprehensive eye examinations including pressure measurement and nerve imaging enable early detection of optic nerve damage, allowing prompt treatment to halt progression and maintain lifelong visual function.