Neuro-Ophthalmology: Understanding the Complex Link Between the Eye and the Brain

Vision is often thought of as a function of the eyes alone, but in reality, we see with our brains. The eyes act as the camera, capturing light and images, but the brain serves as the computer that processes this data into the visual reality we experience. The transmission cable connecting these two vital organs is the optic nerve. When a disruption occurs anywhere along this complex pathway, from the optic nerve to the visual cortex in the brain, it falls under the medical subspecialty of neuro-ophthalmology.

Neuro-ophthalmology merges the fields of neurology and ophthalmology. It focuses on the evaluation, diagnosis, and management of visual problems that originate from the nervous system rather than the eye's physical structure. These conditions often present complex symptoms such as unexplained visual loss, double vision, or abnormal eye movements.

Because the optic nerve and the pathways to the brain are susceptible to a wide range of systemic health issues including strokes, inflammation, tumors, and autoimmune disorders, neuro-ophthalmic conditions often serve as early warning signs for broader health concerns. Understanding the intricate relationship between the eye and the central nervous system is crucial for diagnosing and treating these often sight-threatening conditions.

The Anatomy of Vision: The Neural Pathway

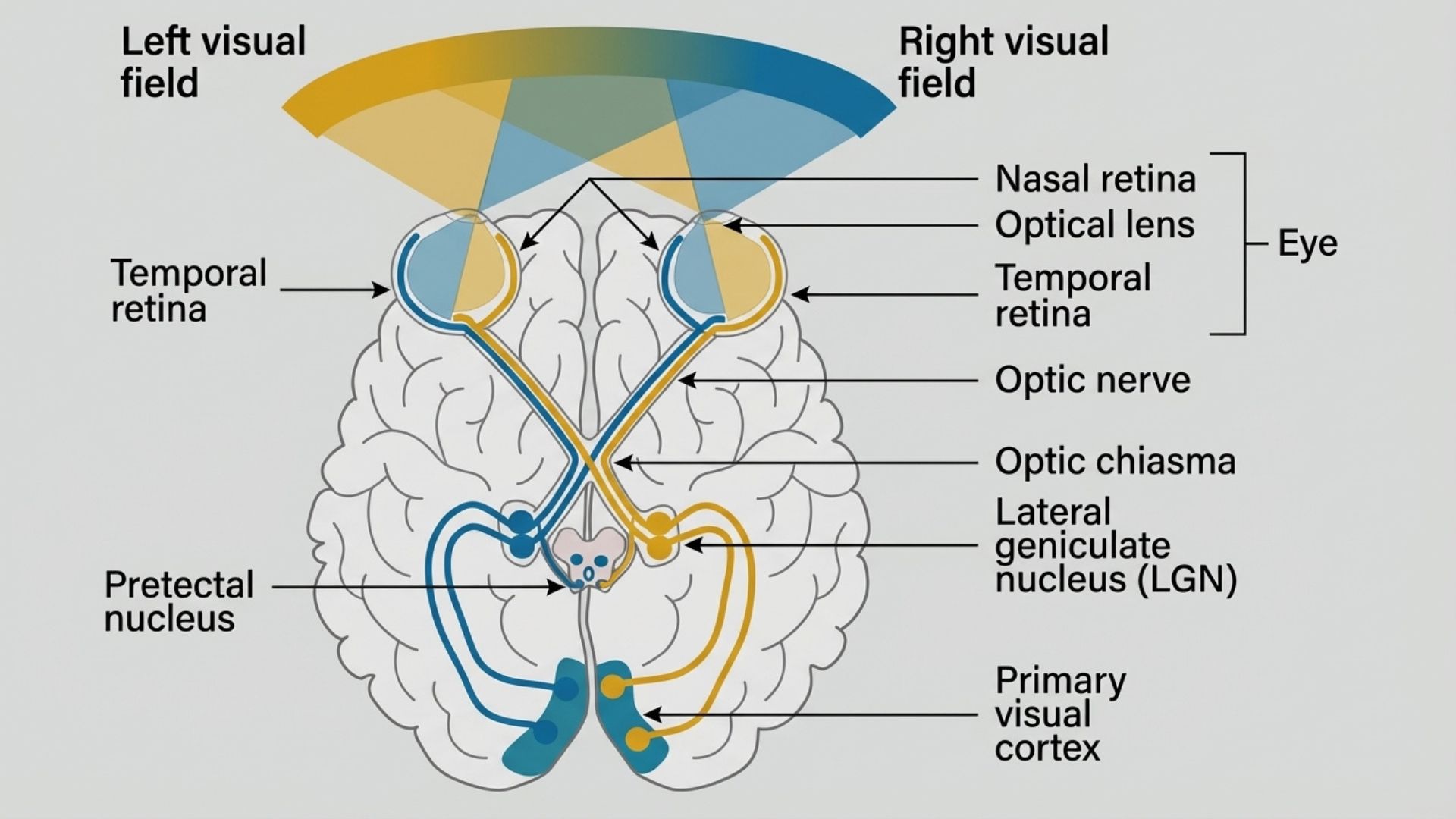

To understand neuro-ophthalmic conditions, one must appreciate the journey of a visual signal. Light enters the eye, passes through the cornea and lens, and hits the retina. Here, photoreceptors convert light into electrical impulses. These impulses travel through the optic nerve, which consists of over a million nerve fibers. The two optic nerves meet at the optic chiasm, where nasal fibers cross over to the opposite side of the brain. The signals then travel via the optic tracts to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe at the back of the brain.

Any lesion, compression, inflammation, or lack of blood supply along this visual highway can result in specific patterns of vision loss. Neuro-ophthalmologists are trained to interpret these patterns to localize the problem within the brain or nervous system. For a detailed anatomical overview of the cranial nerves involved in vision, refer to this National Institute of Health resource.

Common Neuro-Ophthalmic Conditions

The spectrum of neuro-ophthalmic disorders is vast. Below are detailed explanations of the most frequently encountered conditions, ranging from inflammatory diseases to circulation problems affecting the optic nerve.

1. Optic Neuritis

Optic Neuritis is an inflammation of the optic nerve. It is often the presenting symptom of demyelinating diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis, though it can also result from infections or autoimmune disorders. The inflammation damages the protective myelin sheath covering the nerve fibers, slowing or blocking visual signals.

Symptoms include sudden loss of vision usually in one eye, pain on eye movement (a hallmark symptom occurring because the optic nerve sheath shares attachment with the eye muscles), dyschromatopsia (washed-out color vision), and visual field defects.

The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial was a landmark study that established protocols for managing this condition, highlighting the importance of visual field testing in monitoring recovery. Research has shown that early intervention with corticosteroids can significantly improve visual outcomes in patients with optic neuritis.

2. Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

Often described as a stroke of the optic nerve, Ischemic Optic Neuropathy occurs when blood flow to the optic nerve is interrupted, causing damage to the nerve fibers. Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy is the most common form in older adults, typically associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, and sleep apnea. Patients typically wake up with painless vision loss in one eye.

Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy is a medical emergency caused by Giant Cell Arteritis, an inflammation of the arteries. Without immediate treatment, it can rapidly cause blindness in both eyes. Studies published in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology have documented the importance of rapid diagnosis and treatment in preserving vision.

3. Papilledema and Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Papilledema refers specifically to the swelling of the optic disc caused by increased intracranial pressure. The optic nerve is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid, and when pressure in the brain rises, it compresses the nerve, causing the disc to swell.

A common condition seen in neuro-ophthalmology is Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension, formerly known as pseudotumor cerebri. This condition mimics the symptoms of a brain tumor but is caused by high CSF pressure without a mass lesion. It most commonly affects women of childbearing age who are overweight.

Symptoms include headaches (often worse in the morning), transient visual obscurations (vision blacking out for seconds), pulsatile tinnitus (whooshing sound in the ears), and double vision (often due to 6th cranial nerve palsy).

Advanced imaging, particularly Optical Coherence Tomography, is vital for distinguishing papilledema from pseudopapilledema and for monitoring the thickness of the Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer. Research from the National Eye Institute has demonstrated that OCT measurements provide quantifiable data for tracking disease progression and treatment response.

4. Cranial Nerve Palsies

The movement of the eyes is controlled by three cranial nerves: the third (oculomotor), fourth (trochlear), and sixth (abducens) nerves. If any of these nerves are weakened or paralyzed due to ischemia, trauma, or compression, the eyes become misaligned.

Third nerve palsy can cause a droopy eyelid, an eye that drifts outward, and sometimes an enlarged pupil. A painful third nerve palsy can be a sign of a brain aneurysm and requires emergency attention. Fourth nerve palsy causes the eye to drift upward, leading to vertical double vision. Patients often tilt their head to compensate. Sixth nerve palsy prevents the eye from turning outward, causing horizontal double vision.

These conditions are frequently associated with microvascular disease in patients with diabetes or high blood pressure. According to research published in JAMA Ophthalmology, careful evaluation of cranial nerve palsies can reveal underlying systemic conditions requiring immediate medical attention.

5. Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia Gravis is an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder that causes weakness in the skeletal muscles. The eyes are often the first part of the body to be affected. The condition blocks the transmission of nerve impulses to muscles.

Symptoms include variable ptosis (droopy eyelids that worsen later in the day or when tired), double vision that fluctuates, and Cogan's Twitch (a momentary twitch of the eyelid when looking down then up).

The diagnosis often involves specialized testing including acetylcholine receptor antibody tests and electrophysiological studies. Information from the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation provides valuable resources for understanding this complex autoimmune condition.

6. Thyroid Eye Disease

Associated with autoimmune thyroid disorders, this condition causes the muscles and fatty tissue behind the eye to become inflamed and swollen. This pushes the eye forward and restricts eye movement.

Symptoms include bulging eyes, retraction of the eyelids (staring appearance), double vision due to muscle restriction, and in severe cases, compression of the optic nerve leading to vision loss. For more information on autoimmune impacts on vision, refer to the American Thyroid Association. Recent studies in ophthalmology journals have highlighted the importance of coordinated care between endocrinologists and ophthalmologists.

Diagnostic Procedures in Neuro-Ophthalmology

Diagnosing neuro-ophthalmic conditions requires a meticulous combination of clinical examination and advanced technology. The goal is to determine whether the issue lies in the eye, the nerve, or the brain.

Visual Field Assessment

Visual field testing is the cornerstone of neuro-ophthalmic diagnosis. It maps the peripheral and central vision to detect blind spots that the patient may not consciously notice. The patient sits before a dome-shaped machine and focuses on a central light. Flashes of light of varying intensity appear in different locations, and the patient presses a button when they see them.

The pattern of field loss helps localize the lesion. For example, a defect in the outer half of the vision in both eyes points to a problem at the optic chiasm, such as a pituitary tumor. As noted in research regarding visual fields in neuro-ophthalmology, standard automated perimetry is essential for monitoring conditions like optic neuritis. The American Academy of Ophthalmology provides extensive guidelines on proper visual field testing techniques.

Optical Coherence Tomography

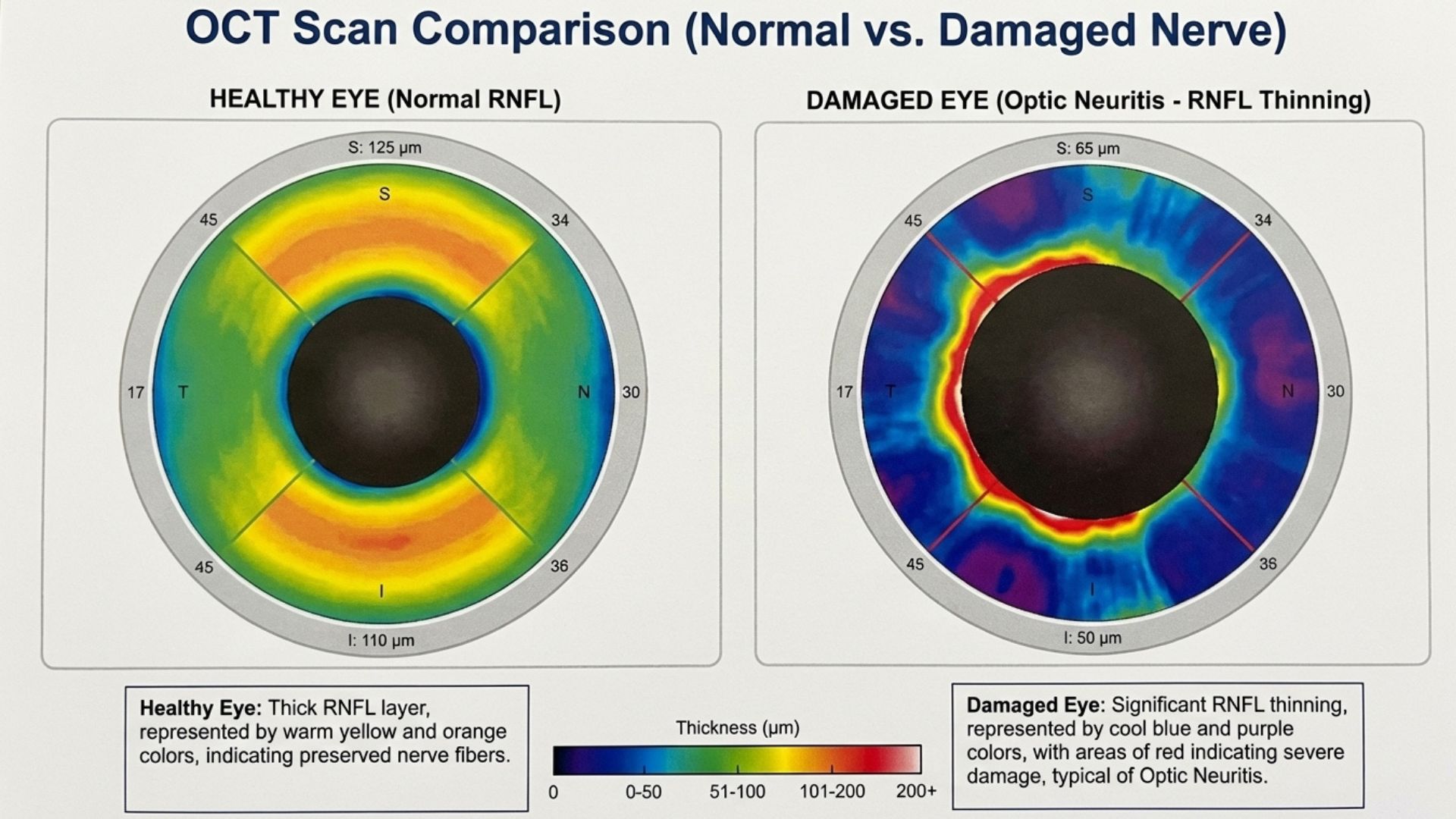

OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique that uses light waves to take cross-section pictures of the retina. In neuro-ophthalmology, it provides objective quantification of the optic nerve head and the Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer.

OCT is highly sensitive in detecting the thickening of the RNFL caused by swelling and can track subtle changes in intracranial pressure better than a standard eye exam.

In conditions like optic neuritis, the OCT can detect thinning of the RNFL and the Ganglion Cell Layer, which correlates with permanent nerve damage. It helps distinguish true papilledema from Optic Disc Drusen.

Research published in Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science has demonstrated that OCT measurements correlate strongly with functional vision outcomes in neuro-ophthalmic diseases.

Electrophysiological Testing

Visual Evoked Potential measures the electrical signal generated by the brain in response to a visual stimulus. It assesses the integrity of the entire visual pathway and is particularly useful in diagnosing optic neuritis, even when the MRI is normal. Electroretinogram tests the function of the retinal cells and helps distinguish whether vision loss is due to a retinal problem or an optic nerve problem.

Studies from the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision have established standardized protocols for these essential diagnostic tests.

Neuro-Imaging

When a neuro-ophthalmologist suspects a structural cause such as a tumor, aneurysm, stroke, or inflammation, an MRI of the brain and orbits is often ordered. MRI provides detailed images of soft tissues and is superior for viewing the optic nerve and demyelinating lesions. Guidelines from the Radiological Society of North America emphasize the importance of appropriate imaging protocols specifically tailored for neuro-ophthalmic conditions.

Ocular Motility and Pupil Testing

The cover-uncover test is used to analyze eye alignment and determine the specific muscles involved in double vision. The pupillary exam checks for an Afferent Pupillary Defect. If one pupil reacts differently to light than the other, it is a strong indicator of optic nerve damage in that eye. The swinging flashlight test remains one of the most valuable clinical signs in neuro-ophthalmology, as documented in numerous studies published in clinical ophthalmology journals.

Treatments and Management Strategies

The management of neuro-ophthalmic conditions depends entirely on the underlying cause. Treatment aims to restore vision, prevent further loss, and manage symptoms.

Medical Interventions

High-dose steroids (often administered intravenously initially, followed by oral taper) are the standard treatment for inflammatory conditions like optic neuritis and Giant Cell Arteritis. They work by rapidly reducing inflammation to prevent permanent nerve damage. Research from the Cochrane Database has established evidence-based protocols for corticosteroid use.

For conditions like Myasthenia Gravis or recurrent optic neuritis, long-term medications to suppress the immune system may be necessary to prevent flare-ups. Studies published in Brain: A Journal of Neurology have demonstrated the effectiveness of various immunosuppressive agents.

For Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension, treatment focuses on lowering CSF pressure. Acetazolamide is commonly prescribed to reduce CSF production. Significant weight reduction is often the most effective long-term remedy for IIH, with studies showing it can put the disease into remission. Research from the Journal of Neurology has documented substantial improvement with weight loss of 5 to 10 percent of body weight.

Surgical Interventions

In cases of severe IIH where vision is threatened despite medication, a surgeon may cut small slits in the optic nerve sheath to allow cerebrospinal fluid to drain, relieving pressure on the nerve. Clinical outcomes research published in ophthalmology journals has shown good long-term success rates with this procedure.

For patients with permanent double vision due to cranial nerve palsies or Thyroid Eye Disease, eye muscle surgery can realign the eyes once the condition has been stable for several months. In severe Thyroid Eye Disease, orbital decompression may be needed to create more space for the swollen tissue.

Botulinum toxin injections are a primary medical treatment for blepharospasm (uncontrollable eyelid squeezing) and hemifacial spasm. The toxin is injected into the eyelid muscles to temporarily paralyze them and stop the spasms.

Optical and Lifestyle Remedies

For patients with double vision, special prism lenses can be ground into spectacles. Prisms bend light to align the images from both eyes, eliminating double vision without surgery.

For patients with permanent visual field loss or reduced acuity, low vision specialists can prescribe magnifiers, telescopic lenses, and contrast-enhancing filters to maximize remaining vision. Resources from the American Foundation for the Blind provide valuable information on assistive devices.

Since conditions like ischemic optic neuropathy and cranial nerve palsies are often linked to vascular health, managing systemic factors is a key part of the remedy. This includes strict control of blood pressure and blood sugar, treatment of high cholesterol, diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea, and smoking cessation. Guidelines from the American Heart Association emphasize the importance of comprehensive cardiovascular risk factor management.

To manage debilitating double vision temporarily, patching one eye is a simple but effective remedy to allow the patient to function until the condition resolves or is treated.

The Importance of Early Detection

Many neuro-ophthalmic conditions are time-sensitive. Sudden loss of vision or the onset of double vision should never be ignored. Early intervention, whether it is steroids for inflammation or acute care for a stroke, can make the difference between recovery and permanent blindness. Regular screening, including visual field tests and OCT scans, allows clinicians to detect subtle progression in chronic conditions.

Studies from The New England Journal of Medicine have repeatedly demonstrated that the timing of intervention is critical in neuro-ophthalmic emergencies, with outcomes significantly better when treatment is initiated within hours of symptom onset.

If you are experiencing symptoms such as sudden vision loss, pain with eye movement, double vision, or unequal pupils, it requires immediate assessment by a qualified specialist. Our ophthalmology specialists are trained in diagnosing and managing complex neuro-ophthalmic conditions.

Important Medical Notice: This information provides general educational content about neuro-ophthalmology and should not replace professional medical advice. For personalized assessment and treatment recommendations, please schedule a consultation with our eye care specialists. All vision treatments including medications and surgical procedures carry risks and limitations. Corticosteroids can cause side effects including elevated blood sugar and bone loss. Surgical interventions carry risks including infection, vision loss, need for additional procedures, and in rare cases permanent blindness. All options should be thoroughly discussed with a qualified ophthalmologist.

Licensed Healthcare Service: Our clinic operates in accordance with healthcare regulations. For questions about our services or to book an appointment, please visit our contact page or call during operating hours. For medical emergencies, contact emergency services immediately.

When to Seek Professional Care

Progressive damage to the optic nerve can cause sudden vision loss, double vision, or abnormal eye movements, often signalling neurological conditions requiring urgent evaluation. Please visit the doctor if you have any of the following symptoms:

Sudden unexplained loss of vision in one eye

Persistent double vision or misaligned eye movements

Pain when moving the eyes accompanied by visual changes

Flashing lights or temporary vision blackouts

Unequal pupil size or abnormal pupil reactions

Prompt neuro-ophthalmic assessment enables accurate diagnosis of complex vision disorders, prevents permanent visual damage, and addresses potentially serious underlying conditions through targeted medical or surgical treatment.